CONCEPT OF KOHLBERG THEORY

Hemming, in his book, ‘The Development of Children’s Moral Values’ writes, “Moral development is the process in which the child acquires the values esteemed by his community, acquires a sense of right and wrong in terms of these values, learns to regulate his personal desires and compulsions so that, when a situational conflict arises, he does what he ought to do rather than what he wants to do. Moral development is the process by which a community seeks to transfer the egocentricity of the baby into the social behavior of the mature adult.

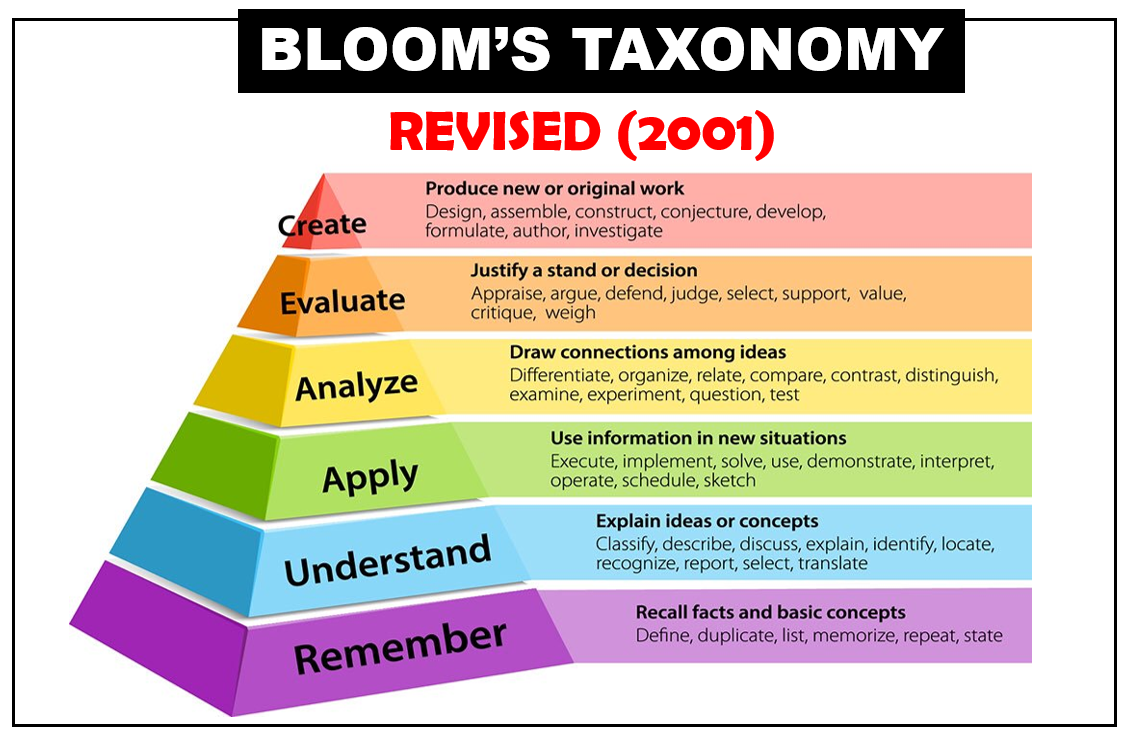

Jean Piaget introduced the idea of how moral development occurs in stages, each level built on life experiences and active reasoning. Lawrence Kohlberg (1927-1983) an American psychologist furthered this idea by examining how moral reasoning changes as we grow.

.jpg)

Kohlberg extended Piaget's theory, proposing that moral development is a continual process that occurs throughout the lifespan, but was more centered on explaining how children develop moral reasoning. Kohlberg believed that moral development, like cognitive development, follows a series of stages. His theory outlines six stages of moral development within three different levels.

Kohlberg's theory proposes that there are three levels of moral development, with each level split into two stages. Kohlberg suggested that people move through these stages in a fixed order, and that moral understanding is linked to cognitive development. The three levels of moral reasoning include preconventional, conventional, and postconventional. People can only pass through these levels in the order listed. Each new stage replaces the reasoning typical of the earlier stage. Not everyone achieves all the stages.

IMPORTANT CONCEPTS OF KOHLBERG MORAL DEVELOPMENT THEORY

(1) Moral Realism

Rules are fixed and rigid we cannot break the rules. if we break the rules we get punishment.

Example: If you break the traffic signal rules you get punishment

(2) Moral Cooperation

If your intention is right you can break the rules

Example: If you break the traffic signal rules by allowing the ambulance to pass through.

(3) Moral Dilemma

Confusion between the right and wrong

Example: You have an SSC, Bank and Teaching Exam on the same day you might have confused to choose the right one

(4) Moral Reasoning

It is a thinking process involved in the judgement of question of right and wrong

Example: Vote for the right Politician is moral reasoning

(5) Morality

Recognition of the distinction between good and evil or between right and wrong; respect for and obedience to the rules of right conduct; the mental disposition or characteristic of behaving in a manner intended to produce good results.

HOW KOHLBERG DEVELOPED HIS THEORY

Kohlberg used Piaget’s storytelling technique to tell people stories involving moral dilemmas. In each case, he presented a choice to be considered, for example, between the rights of some authority and the needs of some deserving individual who is being unfairly treated. Participants were also interviewed to determine the reasoning behind their judgments in each scenario.

One of the best known of Kohlberg’s (1958) stories concerns a man called Heinz who lived somewhere in Europe.

"A man named Heinz, who lived in Europe, had a wife whom he loved very much. His wife was diagnosed with a rare type of cancer and did not have long to live. Luckily, there was a pharmacist who invented a drug called radium that could cure her. The pharmacist owned all rights to this medication and decided to sell it at a high markup in order to make a profit. While it cost only $200 to make, he sold it for 10 times that amount: $2000. Heinz did not have enough money to pay the exorbitant price, so he tried fundraising to cover the costs. With time running out, he had only managed to gather $1000, which was not enough to buy the medication. Heinz explained to the chemist that his wife was dying and begged the pharmacist if he could have the drug cheaper or pay the rest of the money later but the man refused. Desperate and running out of time, Heinz broke into the pharmacy after hours and stole the drug to save his wife."

Kohlberg asked a series of questions such as:

(1) Should Heinz have stolen the drug?

(2) Would it change anything if Heinz did not love his wife?

(3) What if the person dying was a stranger, would it make any difference?

(4) Should the police arrest the chemist for murder if the woman died?

By studying the answers from children of different ages to these questions, Kohlberg hoped to discover how moral reasoning changed as people grew older. The sample comprised 72 Chicago boys aged 10–16 years, 58 of whom were followed up at three-yearly intervals for 20 years (Kohlberg, 1984).

Each boy was given a 2-hour interview based on the ten dilemmas. What Kohlberg was mainly interested in was not whether the boys judged the action right or wrong, but the reasons given for the decision. He found that these reasons tended to change as the children got older. He then classified their reasoning into the stages of his theory of moral development.

STAGES OF MORAL DEVELOPMENT

Kohlberg's theory is broken down into three distinct levels of moral reasoning:

(1) Preconventional Morality

(2) Conventional Morality

(3) Postconventional Morality

People can only pass through these levels in the order listed. At each level of moral development, there are two stages which provide the basis for moral development in various contexts. Each new stage replaces the reasoning typical of the earlier stage. Similar to how Piaget believed that not all people reach the highest levels of cognitive development, Kohlberg believed not everyone progresses to the highest stages of moral development.

LEVEL 1 : PRECONVENTIONAL MORALITY

Preconventional morality is the earliest period of moral development. It lasts until approximately the age of 9. At this age, children don’t have a personal code of morality, their decisions are primarily shaped by the expectations of adults and the consequences for following or breaking the rules.

For example, if an action leads to punishment is must be bad, and if it leads to a reward is must be good.

A child with pre-conventional morality has not yet adopted or internalized society’s conventions regarding what is right or wrong, but instead focuses largely on external consequences that certain actions may bring. Hence, the authority is outside the individual and children often make moral decisions based on the physical consequences of actions.

The two stages at this level are:

Stage 1 : Obedience and Punishment

(How can I avoid punishment?)

The earliest stages of moral development, obedience and punishment are especially common in young children, but adults are also capable of expressing this type of reasoning. According to Kohlberg, people at this stage see rules as fixed and absolute. Obeying the rules is important because it is a way to avoid punishment.

For example, an action is perceived as morally wrong because the perpetrator is punished; the worse the punishment for the act is, the more “bad” the act is perceived to be.

Stage 2 : Individualism and Exchange

(What’s in it for me? aiming at a reward.)

This stage is also known as : Instrumental Orientation or TIT for TAT stage.

At this stage of moral development, children account for individual points of view and judge actions based on how they serve individual needs. In the Heinz dilemma, children argued that the best course of action was the choice that best served Heinz’s needs.

Hence this stage of reasoning shows a limited interest in the needs of others, only to the point where it might further the individual’s own interests. As a result, concern for others is not based on loyalty or intrinsic respect, but rather a “you scratch my back, and I’ll scratch yours” mentality.

Elementary school children think, if you break my pencil I will break yours (Tit for Tat).

Reciprocity is possible at this point in moral development, but only if it serves one's own interests like Sharing tiffin (Individualism and Exchange).

LEVEL 2 : CONVENTIONAL MORALITY

The next period of moral development is marked by the acceptance of social rules regarding what is good and moral. Throughout the conventional level, a child’s sense of morality is tied to personal and societal relationships. During this time, adolescents and adults internalize the moral standards they have learned from their role models and from society.

This period also focuses on that the authority is internalized but not questioned, and reasoning is based on the norms of the group to which the person belongs. A social system that stresses the responsibilities of relationships as well as social order is seen as desirable and must, therefore, influence our view of what is right and wrong.

The two stages at this level are:

Stage 3 : Developing Good Interpersonal Relationships

(Social norms, good boy – good girl attitude.)

This stage of the interpersonal relationship of moral development is focused on living up to social expectations and roles. The child/individual is good in order to be seen as being a good person by others, i.e., children want the approval of others and act in ways to avoid disapproval. There is an emphasis on conformity, being "nice," and consideration of how choices influence relationships.

In Kohlberg’s study as in the example above, they accepted that Heinz should steal the medicine and “he was a good man for wanting to save his wife.” They also reasoned that “his intentions were good, that of saving the life of someone he loves.”

Stage 4 : Maintaining Social Order

(Law and order morality.)

This stage is focused on ensuring that social order is maintained. At this stage of moral development, people begin to consider society as a whole when making judgments. The child/individual becomes aware of the wider rules of society, so judgments concern obeying the rules in order to uphold the law and to avoid guilt. The focus is on following the rules, doing one’s duty, and respecting authority.

Moral reasoning in stage four is beyond the need for individual approval exhibited in stage three. If one person violates a law, perhaps everyone would—thus there is an obligation and a duty to uphold laws and rules. Most active members of society remain at stage four, where morality is still predominantly dictated by an outside force.

Pertaining to the example above, participants in stage four would argue that while they understood why he wanted to steal the medication, they could not support the idea of theft. Society cannot maintain order if its members decided to break the laws when they thought they had a good enough reason to do so.

LEVEL 3 : POSTCONVENTIONAL MORALITY

At this level of moral development, people develop an understanding of universal ethical principles and values of morality. These are abstract and ill-defined, but might include: the preservation of life at all costs, and the importance of human dignity.

This level is marked by a growing realization that individuals are separate entities from society and that individuals may disobey rules inconsistent with their own principles. Individual judgment is based on self-chosen principles, and moral reasoning is based on individual rights and justice. According to Kohlberg this level of moral reasoning is as far as most people get.

Post-conventional moralists live by their own ethical principles—principles that typically include such basic human rights as life, liberty, and justice—and view rules as useful but changeable mechanisms, rather than absolute dictates that must be obeyed without question.

Because post-conventional individuals elevate their own moral evaluation of a situation over social conventions, their behavior, especially at stage six, can sometimes be confused with that of those at the pre-conventional level. Some theorists have speculated that many people may never reach this level of abstract moral reasoning.

The two stages at this level are:

Stage 5 : Social Contract and Individual Rights

(Justice and the spirit of the law.)

The ideas of a social contract and individual rights cause people in the next stage to begin to account for the differing values, opinions, and beliefs of other people. Rules of law are important for maintaining a society, but members of the society should agree upon these standards.

In this stage, the world is viewed as holding different opinions, rights, and values. Laws are regarded as social contracts rather than rigid edicts. Those that do not promote the general welfare should be changed when necessary to meet the greatest good for the greatest number of people.

Reflecting on the morals and ethics of their current community allows them to address inconsistencies in their values and attempt to fix what they do not agree with. Democratic government is theoretically based on stage five reasoning.

This is one step ahead of stage four, where the main goal is to keep a society functioning at all costs.

For example, in Heinz’s dilemma, the man should steal the medication for his wife because she is deathly ill. The protection of life is more important than breaking the law against stealing and because also the laws do not take the circumstances into account.

Stage 6 : Universal Principles

(Principled conscience)

Kohlberg’s final level of moral reasoning is based on universal ethical principles and abstract reasoning. People at this stage have developed their own set of moral guidelines which may or may not fit the law. People follow these internalized principles of justice, even if they conflict with laws and rules.

The individual acts because it is morally right to do so (and not because he or she wants to avoid punishment), it is in their best interest, it is expected, it is legal, or it is previously agreed upon. Although Kohlberg insisted that stage six exists, he found it difficult to identify individuals who consistently operated at that level.

E.g., human rights, justice, and equality. The person will be prepared to act to defend these principles even if it means going against the rest of society in the process and having to pay the consequences of disapproval and or imprisonment, like Subhash Chandra Bose, Lal Bahadur Shastri, Bhagat Singh etc.

In the Kohlberg's Heinz example, it is okay for the man to take the medication without paying as objects or property are not as valuable as his wife’s life.

In other sense, A person take risk of their own life for save others life. For example, in Madhya Pradesh, A police constable save 400 school children, A bomb was found in school at that time there was no bomb disposal squad at hand so, he ran for 1km with 10 kg bomb in his arms to save the children present in school.

CRITICISMS OF KOHLBERG'S THEORY

Kohlberg's theory played an important role in the development of moral psychology. While the theory has been highly influential, aspects of the theory have been critiqued for a number of reasons.

PROBLEMS WITH KOHLBERG'S METHODS

(1) The Dilemmas are Artificial

Most of the dilemmas are unfamiliar to most people (Rosen, 1980). For example, it is all very well in the Heinz dilemma asking subjects whether Heinz should steal the drug to save his wife.

However, Kohlberg’s subjects were aged between 10 and 16. They have never been married, and never been placed in a situation remotely like the one in the story. How should they know whether Heinz should steal the drug?

(2) The Sample is Biased

According to Carol Gilligan (1977), a research assistant of Kohlberg, criticized her former mentor’s theory because Kohlberg’s theory was based so narrowly on an all-male samples, the stages reflect a male definition of morality (it’s androcentric). Mens' morality is based on abstract principles of law and justice, while womens' is based on principles of compassion and care.

Further, the gender bias issue raised by Gilligan is a reminded of the significant gender debate still present in psychology, which when ignored, can have a large impact on the results obtained through psychological research.

(3) The Dilemmas are Hypothetical

In a real situation, what course of action a person takes will have real consequences – and sometimes very unpleasant ones for themselves. Would subjects reason in the same way if they were placed in a real situation? We just don’t know.

The fact that Kohlberg’s theory is heavily dependent on an individual’s response to an artificial dilemma brings a question to the validity of the results obtained through this research.

People may respond very differently to real life situations that they find themselves in than they do with an artificial dilemma presented to them in the comfort of a research environment.

(4) Poor Research Design

The way in which Kohlberg carried out his research when constructing this theory may not have been the best way to test whether all children follow the same sequence of stage progression.

His research was cross-sectional, meaning that he interviewed children of different ages to see what level of moral development they were at.

PROBLEMS WITH KOHLBERG'S THEORY

(1) Are there Distinct Stages of Moral Development?

Kohlberg claims that there are, but the evidence does not always support this conclusion. For example, a person who justified a decision on the basis of principled reasoning in one situation (postconventional morality stage 5 or 6) would frequently fall back on conventional reasoning (stage 3 or 4) with another story.

In practice, it seems that reasoning about right and wrong depends more upon the situation than upon general rules.

What is more, individuals do not always progress through the stages and Rest (1979) found that one in fourteen actually slipped backward.

The evidence for distinct stages of moral development looks very weak, and some would argue that behind the theory is a culturally biased belief in the superiourity of American values over those of other cultures and societies.

(2) Does Moral Judgment match Moral Behavior?

Kohlberg never claimed that there would be a one to one correspondence between thinking and acting (what we say and what we do) but he does suggest that the two are linked.

However, Bee (1994) suggests that we also need to take account of:

(a) habits that people have developed over time.

(b) whether people see situations as demanding their participation.

(c) the costs and benefits of behaving in a particular way.

(d) competing motive such as peer pressure, self-interest and so on.

Overall Bee points out that moral behavior is only partly a question of moral reasoning. It is also to do with social factors.

(3) Is Justice the most Fundamental Moral Principle?

This is Kohlberg’s view. However, Gilligan (1977) suggests that the principle of caring for others is equally important. Furthermore, Kohlberg claims that the moral reasoning of males has been often in advance of that of females.

Girls are often found to be at stage 3 in Kohlberg’s system (good boy-nice girl orientation) whereas boys are more often found to be at stage 4 (Law and Order orientation). Gilligan replies:

“The very traits that have traditionally defined the goodness of women, their care for and sensitivity to the needs of others, are those that mark them out as deficient in moral development”.

In other words, Gilligan is claiming that there is a sex bias in Kohlberg’s theory. He neglects the feminine voice of compassion, love, and non-violence, which is associated with the socialization of girls.

Gilligan concluded that Kohlberg’s theory did not account for the fact that women approach moral problems from an ‘ethics of care’, rather than an ‘ethics of justice’ perspective, which challenges some of the fundamental assumptions of Kohlberg’s theory.

However, longitudinal research on Kohlberg’s theory has since been carried out by Colby et al. (1983) who tested 58 male participants of Kohlberg’s original study. She tested them six times in the span of 27 years and found support for Kohlberg’s original conclusion, which we all pass through the stages of moral development in the same order.

EDUCATIONAL IMPLICATIONS OF KOHLBERG’S THEORY OF MORAL DEVELOPMENT

Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development has come into the notice of educators across the globe. Many of them see Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development as a response to the confusion they had regarding moral education.

Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development lays down an exhaustive approach that allows one to understand the moral maturity of an individual and at the same time provides a process through which the moral development of an individual can be further enhanced.

The concerns on which Kohlberg has laid emphasis in his theory have important implications for education which are as follows:

Kohlberg’s Stage 1 and Early Childhood Education

Most preschool and some kindergarten students are still in the first stage of moral development, according to Kohlberg’s theory. In this stage, it is important to begin to lay the groundwork to encourage moral behaviors.

In stage 1, young children are primarily motivated to behave appropriately simply to avoid being punished for misbehaving. By understanding this stage of moral development, teachers can help to guide their student’s moral development by setting a code of conduct for the classroom to encourage good behavior.

For young children who are still in the first stage of moral development, it is important to set clear guidelines for behavior, and clear consequences for misbehavior. It is important to stay consistent with the code of conduct and punishment system throughout the school year.

For young children, it is important to implement clear punishments, such as loss of privileges, for students who break classroom rules. This could include taking away free choice time for students who break the rules.

Teacher can also start to offer rewards for children who follow the rules at this level. As they progress toward stage 2 of level 1, they will become more motivated to follow the rules if an enticing reward is offered.

Kohlberg’s Stage 2 and Early Elementary School

By stage 2, young children become more motivated to behave and follow the rules if they are offered a reward for doing so. Implementing a system to reward elementary students who follow the classroom rules and who exhibit helpful behaviors in the classroom can go a long way in encouraging moral behavior.

At this stage, children understand that behaviors that are punished are considered “bad,” and that behaviors that are rewarded are considered “good.”

Students also begin to learn that different people have different points of view at this stage. They consider what is best for the individual (themselves) to be what is right, however, they also begin to see the need for mutual benefit. They begin to learn that others will treat them well if they in turn treat others well. They begin to see morality in terms of helping others for their own self-interest.

At this stage, it is a good idea to introduce classroom activities that encourage cooperation between students. Games and assignments that require students to help one another in order to succeed will help students at this stage to further develop their moral reasoning skills.

Kohlberg’s Stage 3 and Late Elementary/Middle School

Most children reach stage 3 between the ages of 10 and 13. In this stage, children begin to think more about the other people around them. The consider how their behavior affects other people, and how other people perceive them.

At this stage, you can help to strengthen your students' moral character by allowing them to help you to create a code of conduct for the classroom. This lets the students be partially responsible for the classroom rules, which they will be expected to follow.

At this stage, students begin to think more about how their actions affect others. They may be less inclined to follow school rules if they can’t see a clear benefit to following the rules. By allowing students in this stage to have a hand in creating the code of conduct by discussing how different behaviors affect other students, students will be more willing to follow the rules. At this stage, students may start to become unwilling to blindly follow rules if they don’t understand the reasoning behind them.

At this stage, it is also important to continue to introduce activities and assignments that encourage students to work together toward a common goal to further strengthen your students’ moral character.

Older students may begin to reach stage 4 by the time they reach the end of middle school or the beginning of high school. Allow ample time for group projects and activities that give students at different stages of development the opportunity to work together and to learn how their behaviors affects others in a social context.

CONCLUSION

While Kohlberg's theory of moral development has been criticized, the theory played an important role in the emergence of the field of moral psychology. Researchers continue to explore how moral reasoning develops and changes through life as well as the universality of these stages. Understanding these stages offers helpful insights into the ways that both children and adults make moral choices and how moral thinking may influence decisions and behaviors.

“Being a good person is important in life, when you give good out into the world you will receive it back.”